Education on the Estate

44 of the 101 houses in Kemp Town have in their time been used as schools (almost always boarding schools) as the Brighton Street Directories make clear. Private schools provided big business opportunities for the Victorians: a directory of 1876, for example, tells us that in that year Brighton as a whole contained 55 Gentlemen’s Boarding Schools (4 in Kemp Town) and 87 Ladies’ Boarding Schools (17 in Kemp Town). The last boarders left the estate in 2009 when St Mary’s Hall closed and its boarding house at 22 Sussex Square was sold. The only education that continues is for the benefit of foreign students at 1&2 Sussex Square, where EF Language School have their Brighton premises.

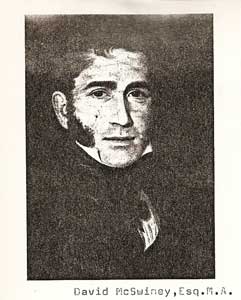

The pioneer of education on the estate was Daniel McSwiney, an Irishman from Cork, who opened the first school at 7 Sussex Square in 1831, but remained there for only 3 years before his premature death at the age 44 in 1834. A classical scholar and aspirant poet he secured in his youth a footnote in literary history by being the tutor to the academically precocious Elizabeth Barrett (later Browning after her marriage to the poet Robert) at Hope End in Malvern, Worcestershire.

[Pic of McSwiney] (Pic of EB Browning)

Just a year after McSwiney started his enterprise, the Rev George Proctor, who had been a master a Lewes Old Grammar School, set up a Young Gentlemen’s Academy at Chichester House at the west end of Chichester Terrace, a house not strictly part of the estate, and which stood in a solitary position until the terrace was completed by Cubitt in the 1850s. The Academy continued under the direction of George Faithful, who had been solicitor to Thomas Kemp, from 1848 to 1850, and then under Rev George Cary until 1861. Local myth has it that this was the model for Dr Blimber’s Academy in Dombey and Son. Dickens regularly stayed in Brighton at the Bedford Hotel in the 1840s (as did Mr Dombey when visiting his son Paul) and so it is not inconceivable that fiction and reality meet in Chichester Terrace. At least the illustration by Phiz gives us a sense of what schoolboys looked like in 1848 when the book was published.

By the middle of the 1860s there was a remarkable density of schools in some parts of the estate. For example on the west side of Sussex Square, numbers 1/2, 4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,13,16,17 and 18 were all schools. The census of 1881 records 99 girls and 43 boys boarding on this side. If we look at 8 Sussex Square, for example, we see that Miss Charlotte Frewer, who was Principal from 1862-96, taught 20 girls with 5 other teachers, which is a generous staffing ratio by any standards. She also employed a cook and 5 maids.

This model is typical: most schools were run by widows assisted by a sister or niece with similar staffing provision. Quite how 30+ people fitted into the confines of a house designed for a family, albeit a large family, remains a matter of conjecture. The largest establishment seems to have been that of Miss Sara Prangley at 17 Lewes Crescent. In 1881, she has 32 girl boarders (aged 10 to 18), 3 teaching staff, a cook and 4 servants. How on earth did 50 of them all manage to live in that house!

What did these children learn whilst at school? We must remember that there was no such thing as legislation over the curriculum in the 19th century. Nowadays education may be a central concern of any government, but schooling only became compulsory in 1880 (for 5-10 year-olds), with the age raised to 11 in 1893 and 12 in 1899. Unless their occupation necessitated boarding, middle and upper class families educated their daughters at home, by means of a governess. Interestingly a number of the girls’ schools in the 1880s referred to their teachers as ‘governesses’, presumably to give parents the impression they were buying into a superior lifestyle for their children. Charlotte Frewer, for example, employed governesses in French, English and German as well as a teacher of music. This gives us a good idea of the sort of accomplishments that would be cultivated in the girls. These governesses of course are only the resident staff. Teachers of drawing, dancing and singing would visit the schools on a peripatetic basis.

Whereas the girls were not being prepared for any academic rigours beyond the social accomplishments demanded by polite society, the boys would be prepared for a public school. The Rev Henry Barclay at 11 Sussex Square and the Rev John Cross at 21 both ran what we now recognise as a prep school for 8 to 13 year-olds. Their curriculum would not extend much beyond the classics, mathematics and divinity in that order. It is unlikely that much attention would be given to the so-called soft subjects that their neighbours in the girls’s schools enjoyed.

Inevitably where schools are concerned, relations with the neighbours can lead to problems. The formidable and litigious Mrs Ann Sober, the widowed sister of Thomas Read Kemp, occupied 22 Sussex Square on the departure of her brother until 1848, when she let it to the Misses Wilmshurst. The new occupants of 22 proposed to start a school there, a plan that the widowed Mrs Kemp, who had moved close by, vigorously blocked, taking out an injunction against her sister-in-law, alleging the school would be a ‘considerable nuisance’ and could well ‘injure her property by diminishing its value.’ The judge agreed that ‘neighbours will suffer annoyance not only from [the girls] practising music and dancing, but from their relations and friends continually calling upon them’. He granted an injunction. The Misses Wilmshurst had to wait 11 years before finally opening their school at 22 Sussex Square in 1859. It continued thus until 1882 and was taken over by St Mary’s Hall as one of its boarding houses in 1923. Thus Kemp’s own house has spent 104 years of its life as a school.

If the 1870s and 80s were the heyday of schools on the estate, the late 90s saw the beginning of their decline with 10 closing. The south coast had always proved popular with London and overseas parents for boarding education for their sons and daughters; the healthy sea air and even the opportunities for sea bathing appealed to Victorian families. Furthermore, the architectural sophistication of the crescent and square had a certain cachet for parents and the enclosures looked attractive, even if the pupils were not allowed in there to play tennis or kick a ball around. The gathering reputation of the new public schools, which are disproportionately prolific in Sussex, were a significant lure for what we might now term aspirational parents. Brighton College founded in 1845, Lancing (1848), Husrtpierpoint (1849), Ardingly (1858) and Eastbourne (1867) all had grand buildings, fine chapels and extensive playing fields, spaces sadly lacking to for most children on the estate. They were convincing imitations of the original public schools such as Eton and Winchester. The mobilisation of the Wimbledon House girls to the impressive new buildings high up on the cliffs at Roedean in 1899 was a significant development in the history of education in Brighton. Parents liked the idea of a prestigious public school for their daughters and thus moved them from the smaller and cramped establishments. In addition to this, Brighton and Hove High School (for day girls) opened in 1875 at the Temple in Montpelier Road, the house built and lived in by Thomas Read Kemp.

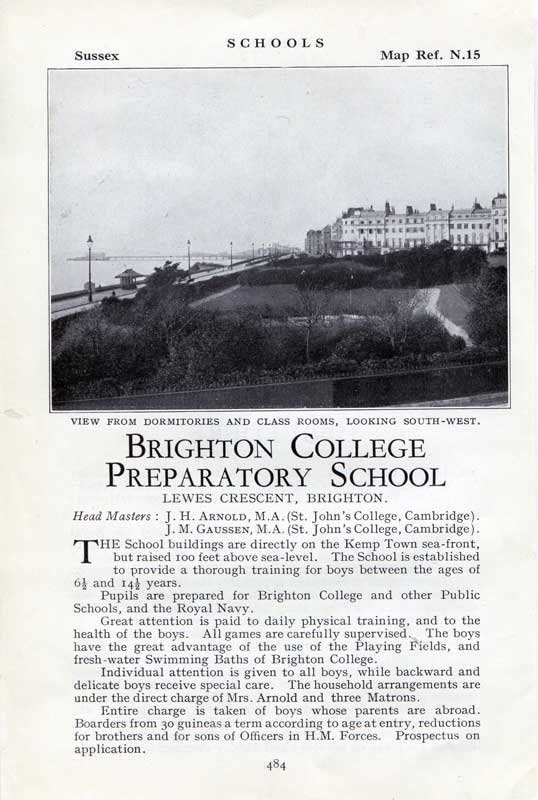

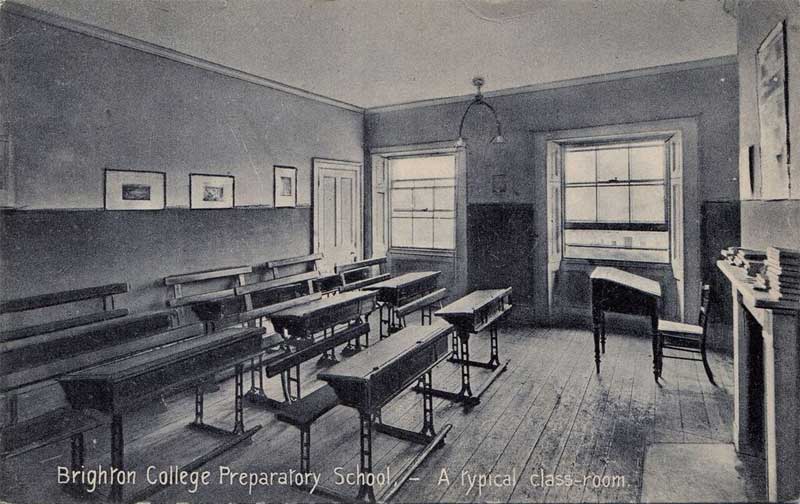

In the 20th century some houses on the estate found themselves becoming more clearly defined as preparatory schools with memorable names for 8 to 13 year-old boys, rather than institutions that attempted to educate the whole age range, such as we found at Chichester House. At 4 Sussex Square the Misses Winder ran Rostellan House from 1898 to 1907 and up at 27 St Kilda’s existed from 1904-06. Across the gardens at 47 Alexander Chalmers Esq, MA ran the grandly named Blenheim House from 1903 to 1916. Brighton College Junior Department occupied 16 Lewes Crescent from 1925 to ’38 and 28 Lewes Crescent as well from 1930 to ’38 before moving to a site opposite the college itself. The prospectus information might apply to any prep school with an eye for the market in this era.

Classroom Brighton College Preparatory School 16 Lewes Crescent

From 1910 to 1915 St Olaf’s Prep School was at 34 Sussex Square. It was run successively by R Morton-York Esq and James Fendall Esq, MA Cantab, in the same premises where only a few years previously Miss Smellie had managed her High Class School of Housewifery, a source of some amusement no doubt to the St Olaf’s boys who had any knowledge of their school’s history.

The onset of the Great War changed the face of the estate. The high-ceilinged rooms on the ground and first floors were no longer filled with school desks but with hospital beds; and children milling about the streets were replaced by the walking wounded. By 1918 there were 13 hospitals of various kinds, chiefly for convalescent officers, most of them in Chichester Terrace or the west side of the crescent. 13 Lewes Crescent, written about elsewhere, was for New Zealand Officers.

Thomas Kemp indeed pursued a grand design when he first drew up plans for his town in 1823. His hope to bring the aristocracy to Brighton was only partly successful. Certainly the Duke of Devonshire, The Marquis of Bristol and Lawrence Peel were long-stayers and had no need to turn their grand houses into schools. But the remaining 98 were expensive places to run and one way for widows to pay the bills after the death of their husbands was to take in children as boarders. With greater economic privations afar the First World War and a smaller pool of young women willing to live a life of below-stairs service, the answer to maintaining the houses was to divide them into flats. But that is another story.

Simon Smith